This year Libya marks ten years since the beginning of anti-government protests, which almost immediately turned into an armed struggle against the army and security forces and entailed an overthrow of that country's leader Muammar Gaddafi. The North African state became yet another and perhaps the most affected victim of the so-called "Arab Spring", which had been raging in the Middle East and North Africa back those days. Somewhere, like in Tunisia, regime changes appeared relatively peaceful. And in Syria, for instance, the crisis is still underway, although the leadership, aided by Russia, managed to cope with and hold out against the several-thousand-strong army of terrorists.

Libya was not that lucky. In February 2011, the country's eastern part experienced the "Day of Anger", when a number of anti-government demonstrations swept through a number of localities. They quickly escalated first into clashes with the military and the police, and then into an armed rebellion. Many servicemen, including high-ranking officers, joined the protesters. The city of Benghazi became Muammar Gaddafi's opponents' pivot post. A few days later, they got a handle on the entire Cyrenaica, a historical region in eastern Libya. The authorities in Tripoli launched a counter-offensive, which proved rather efficient for a start: the rebels were driven back from a number of strategically important cities. But the situation was reversed after the military intervention by a number of Western countries and their allies in the region.

Amid media reports of mass killings and armed suppression of protests by security forces, many of which had never been proved, late February 2011 saw the UN Security Council unanimously adopt Resolution 1970 imposing an arms embargo on Libya. The next document, Resolution 1973 adopted on March 17th, stipulated a no-fly zone over that North African country. Russia abstained on the vote, and none of the veto-holding countries exercised it. Both the decision and the voting pattern are yet to be historically assessed.

Whatever the case, this move by the UN Security Council entailed foreign intervention, with the United States and France playing the lead. As early as on March 19, first bombs fell on Libya. What's interesting, combat aircraft were not only attacked in the air alone, but also on the ground. Under the pretext of creating a no-fly zone, air defense systems and armored vehicles were saturated, as well as civil infrastructure and mass media offices. Needless to say that America and its allies fought the forces of Muammar Gaddafi alone, without harming the so-called rebels.

The outcome is known: the Libyan army was defeated in the following months, the country's leader took refuge in Sirte, and after the October 2011 attack on the city, he was captured and brutally murdered.

These developments, however, have yielded neither democracy nor the associated economic prosperity or human rights respect in Libya. The country quickly descended into chaos. The formal leadership was exercised by the National Transitional Council, established by Muammar Gaddafi's opponents in the early days of insurgency. But as a matter of fact, the situation on the ground was controlled by tribal militias and Islamist groups, including terrorist ones like Al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood (both are banned in Russia). Libya became a transit point for migrants from all over Africa heading to Europe. These processes immediately entailed the formation of criminal structures delivering people to the Mediterranean coast for money at best, and at worst they robbed them, killed them and harvested their organs. Naturally, drug and gun smuggling was flourishing. A benchmark case indicative of the situation in Libya took place in September 2012, when American ambassador Christopher Stevens was killed in an attack against the US Consulate in Benghazi.

The first attempts to get out of the chaos were only made in 2014. In May, General and now Marshal Khalifa Haftar kicked off a military operation in Benghazi against Islamist groups. In June, a parliamentary election was held in Libya, after which most seats were gained by secular forces. But instead of becoming stable, the state split into two centers of power: Tobruk in the east, where the parliament began to hold meetings backed by Khalifa Haftar's army, and Tripoli with basically Islamists holding sway.

In 2015, to overcome the split, agreements to form a Government of National Accord and a Presidential Council were signed in the Moroccan city of Skhirat under the auspices of the UN. The idea was that the country's leading political forces enter the place. In practice, both structures were dominated by the same Islamists. Libya's dual power further augmented, and the country became a platform for score-settling competition between a number of states.

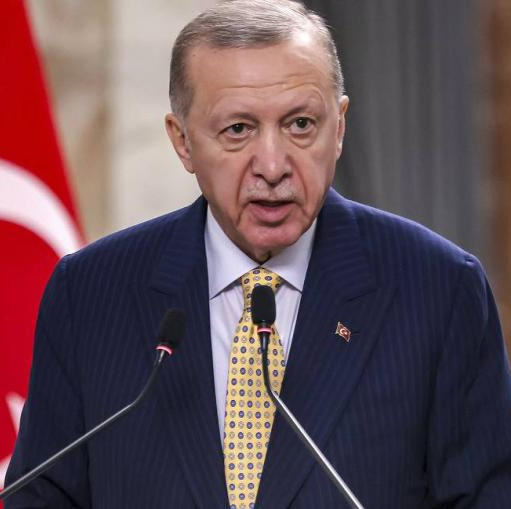

In April 2019, Khalifa Haftar's forces that controlled the country's eastern, southern and most of the western regions, launched an offensive against Tripoli. By the beginning of 2020, all the evidence suggested that the Libyan capital would fall to army onslaught. And January saw Turkey, which had previously signed a memorandum of military cooperation with the Government of National Accord, bring its troops to the country. Following several months of warfare, the Turks and Cabinet-controlled forces managed to drive Khalifa Haftar back from the capital city and dislodge his troops from the southwestern districts to the east.

The front stabilized, and negotiators got down to business. After a series of UN-guided meetings in Morocco, Tunisia and Switzerland, the Libyan political forces managed to elect a new prime minister in February this year. The choice fell on Libyan businessman Abdul Hamid al-Dabaib. He is currently having consultations with various structures to subsequently form a government. In other words, this implies another attempt to pull the country out of the protracted crisis. There are certainly chances for success. On the other hand, there were similar hopes in 2015, when the formation of the Government of National Accord and the Presidential Council were agreed upon. The situation is too fragile to make optimistic forecasts.

Going back to 2011, one can probably understand the Libyans humanwise. Muammar Gaddafi had been ruling the country for over forty years, and the residents naturally accumulated mental fatigue. But, as is typically the case, a violent overthrow of power by grassroots forces, even with active foreign involvement, hardly ever leads to an immediate stabilization or subsequent economic and social prosperity. Libya has been demonstrating this over the past decade. The North African country is exemplary to others, but the lesson has never been learned, as evidenced by what is happening in some other countries.