The Caspian region has every chance to develop into one of Eurasia’s most efficient transport hubs. It shall play an important part in international transit corridors, notably, the North-South corridor and the One Belt, One Road project. The Convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea signed by Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan in Aktau, Kazakhstan, on Monday, will boost the development. The five littoral states declared the Caspian Sea their common internal water body covered by their sovereign and exclusive rights and jurisdiction.

The Convention regulates the member states’ use of the sea, its water, bottom, subsurface area, natural resources and air space. From now on, only ships under the flag of one of the five littoral states will be allowed to navigate the sea, enter it or leave it. Overall, the document, which took the five countries 20 years to agree on, fixes a special legal status to the Caspian as both, a lake and a sea, with a mix of legal norms.

The agreement emphasizes that the member states guarantee the right of “free access from the Caspian Sea to other seas, the world ocean and back, based on generally recognized principles and norms of international law” to ensure transit “for the purpose of expanding international trade and economic development.”

The Convention makes it easier for Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan to take closer positions regarding the development of railways and sea routes within the North-South corridor.

After the construction of the western part of the corridor from the Iranian city of Rasht, the capital of the coastal province of Gilan, to the Astara checkpoint on the Iranian-Azerbaijani border, is completed, it becomes part of the coastal transport infrastructure, facilitating access to the Iranian port of Anzali as well as the Russian and Azerbaijani ports on the Caspian Sea. The eastern part of the railway, from Garmsar to Gorgan and Incheh Borun, where Russian Railways is currently building electric power supply system, goes along the Iranian coast of the Caspian Sea and reaches the border of Turkmenistan. It will help to expand transport and passenger traffic from Iran to Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. Therefore, the two railways are included in the Caspian transit system and at the same time link the region to the transit routes from China and India to Russia and Europe via Iran, Azerbaijan and Central Asia.

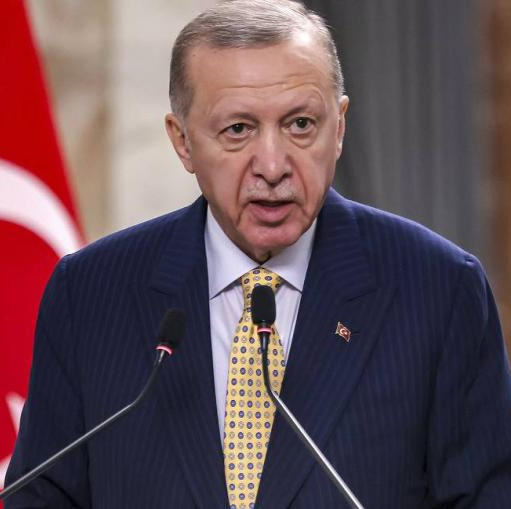

The Caspian region has an enormous potential in this regard. As for now, only one fourth of it is actually utilized. “Despite the great opportunities of the Caspian states, the existing advantages from sea transport are insignificant compared to the facilities that have been built or are under construction,” said [Iranian President] Hassan Rouhani in his speech during the Convention signing ceremony. “The capacity of the Caspian ports is currently about 130 million tons, while the maximum carrying capacity of sea transport is 30 million tons, which is less than 25% of the potential. The Caspian Sea can make transportation of cargoes and passengers cheaper and more convenient, developing the best and most efficient shipping lines between the littoral states. This is why expansion and modernization of seaports may soon be included in the agenda of the littoral states.” In order to expand economic cooperation and develop transit corridors, the Iranian president called for establishing customs unions and a “one-stop customs window,” free economic zones, joint shipping companies and industrial enterprises, as well as expanding banking cooperation and tourism. He also suggested that visa issue procedures should be simplified and ultimately fully abolished.

The parties to the Convention also agreed on fishing quotas. This is particularly important since most sturgeons caught the world are caught in the Caspian Sea.

Like any international document, the Convention is not perfect and is a result of compromise between the Caspian states. However, the parties succeeded in agreeing in principle on such issues like the width of territorial waters (it cannot exceed 15 miles) and the width of fishing area (10 nautical miles adjacent to territorial waters). Within their territorial waters, the littoral states may develop production and exploration of hydrocarbons as they see fit.

However, they failed to agree on demarcation of the bottom and subsurface area and on principles of subsurface usage outside territorial waters. The Convention leaves it up to the parties to resolve these issues on a bilateral basis, taking into account generally accepted principles and norms of international law. Five-party talks on these matters will also continue.

The Caspian bottom is rich in hydrocarbons. Total known oil reserves of the Caspian shelf are about 10 billion tons. Demarcation of the bottom is a sensitive issue, since there are disputed areas where large oil and gas fields have been discovered. Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan cannot agree on the Kapaz (Serdar) oil field. Iran and Azerbaijan claim the part of the bottom under which there is the Sardar-e Jangal oil and gas field with estimated reserves of at least 2 billion bbl. To put it into perspective, Azerbaijan’s entire oil reserves are estimated at 7 billion bbl. The resolution of these issues has been postponed for an indefinite period.

And, of course, another compromise is the clause that allows the parties to “lay underwater pipelines across the bottom of the Caspian Sea.” Russia and Iran objected to such projects in the past. The document actually gives a green light to the construction of the Trans-Caspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan, which is supported by the United States and the European Union. It will deliver gas to Europe along the southern gas corridor, competing with Russian gas. But this seems to be a reasonable concession on the part of the Russian and Iranian diplomacy, which is more than outweighed by the advantages of regional security stipulated by the Convention.